The Write Place: Guides for Writing and Grammar .............................Home

The Write Place: Guides for Writing and Grammar .............................Home  (image from Pixabay)

(image from Pixabay)

Invention as Making Thinking Visible

Writing is not just an expression of your thought, but a re-presentation of it. What's in your head--and heart and spirit--now takes another form (and life) on the page. It's miraculous when you think about it. Your consciousness composed of millions of neural connections and biochemical pathways takes form in language which you express through complex combinations of sounds (speech) or through physical signs called letters. That we have language and are able to express our thinking in the world is among the most important things that define us as human. Learning to develop our understanding and ability to think, and then translate that understanding and thinking into speech or writing, is the goal of education.

Linda Flower in a book called Making Thinking Visible says this about thinking and writing:

To see yourself as a thinker is an important part of being one. To see yourself as a writer who steps back to reflect, as a problem solver who can see options, as a student who can take control of meaning making, [...] is not just an attitude. It is the potent knowledge that one's flow of talk and thought--that rapid, tumbling, sometimes surprising, sometimes confusing flow of thought--is also the rapid generative creation of plans, goals, strategies, and decisions. (23)

Our writing reflects our thinking, but as we learned in the guide on the writing process, it is a fallacy to see writing merely as a transmission of meaning as if we were sending a fax. The writing process, thus, is a thinking process in which we discover or "invent" what we mean to say, as well as the language to say it in, as we work on a piece of writing. As Peter Elbow says, "Think of writing then not as a way to transmit a message but as a way to grow and cook a message" (15).

Invention may have connotations for you of making new creations like Thomas Edison and the light-bulb or researchers inventing a new cure for cancer. But Invention is one of the five canons of classical rhetoric and has been a central part of education in the Western civilization for thousands of years. As Janice Lauer states, "The term invention has historically encompassed strategic acts that provide the discourser with direction, multiple ideas, subject matter, arguments, insights or probable judgments, and understanding of the rhetorical situation" (2). Today we broadly call these strategic acts brainstorming, planning, or pre-writing and place them early in the writing process, often before we ever begin writing. While we might be more involved with generating ideas before we begin writing, writing calls on us to constantly solve problems, make choices, and generate ideas--thus, the entire writing process involves invention. Our language and thinking are constantly evolving in big and small ways as we work on a piece of writing.

So what does it mean to talk about "invention as making thinking visible"? Perhaps another way to communicate this concept is to say this: making thinking visible is a strategy for invention. By making our thinking visible, we can see it, reflect upon it, shape it, organize it, evaluate it, connect it, extend it, problem-solve it. By making our thinking visible it becomes an object which we can manipulate. In our heads, this thinking is invisible. As Ron Ritchart, Mark Church, and Karin Morrison reveal, "When we make thinking visible, we get not only a window into what [we] understand but also how [we] are understanding it" (27).

Donald Murry, from his experience as a Pulitzer Prize author and long-time college writing teacher, believes, "Effective writing is produced from an abundance of specific information" (10). When we put down our thinking (or the thinking of others) we are recording and collecting it, making it visible and specific. But something magical happens as we put down these specifics--they lead to new ideas and connections. Murray describes this generative nature of collecting and putting down our thinking: "It is also information that breeds ideas. Specifics make contact with each other and become an idea. Two and two, in writing, add up to seven" (11). Thus, getting your thinking down--making it visible--is also a way to grow your thinking and so your writing. We certainly need to "brainstorm" and generate ideas as we begin a writing project, but this brainstorming is needed throughout the writing process. We constantly are generating ideas as we make choices and face problems as we write.

Productive invention takes a certain mindset of playfulness and experimentation. If writing is like a performance, your final published draft is like presenting your play before an audience. It is a high stakes, full production with lights, costumes, makeup and a full audience in the seats. If you try to be inventive and brainstorm while imagining you are up on the stage like this you will freeze up. Instead, you need to be free and improvisational. You are not doing the big performance on the stage--the theatre is empty or you are in front of your mirror at home trying different things. For productive invention, you need to let go the stress for perfect performance. Be open. Anything goes and is possible. Don't edit. Don't critique. Just get down your ideas. Importantly, put down as much of your thinking as you can. Be abundant. Keep pushing to get more and more down and out, even when you begin to feel your well is running dry. Seek what the 15th century Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus called "copia" or copiousness and abundance. The goal of this abundance is expansiveness and amplification. One famous exercise he included was writing 150 variations of the same sentence. This type of playfulness and experimentation is not just about getting words down; it is about providing yourself options and space for discovery and innovation. Donald Murry similarly talks about writing 100 or more versions of the title for an article as a way to find not just the best title but one that gets to the heart of what he wants to say.

Inevitably, you will gauge how well what you have put down may work, even as you put something down, but I urge you when you are in this invention phase, not to get hung up on whether something you put down is good or bad. If something is off and terrible, so what. Move on and keep getting ideas down. Nothing is carved in stone at this point, and as Donald Murry says, writers need this abundance; they need this experimental space off the page to get things down and give themselves options and ideas.

Discovery Strategies for Making Thinking Visible Through Invention

The following is a set of heuristic strategies of brainstorming and invention where you make visible your thinking (and the thinking of others). A "heuristic" is defined as "a method or learning or solving problems that allows people to discover things themselves and learn from their own experience" (Cambridge Dictionary). As I say above, by making our thinking visible, we can see it, reflect upon it, shape it, organize it, evaluate it, connect it, extend it, problem-solve it. We can use these strategies to give us the copia, the abundance, the specifics, from which we can shape and build our writing and our thinking. Inevitably, this set of strategies is incomplete, but below are some of the most common and powerful ways for you to generate ideas and make your thinking visible.

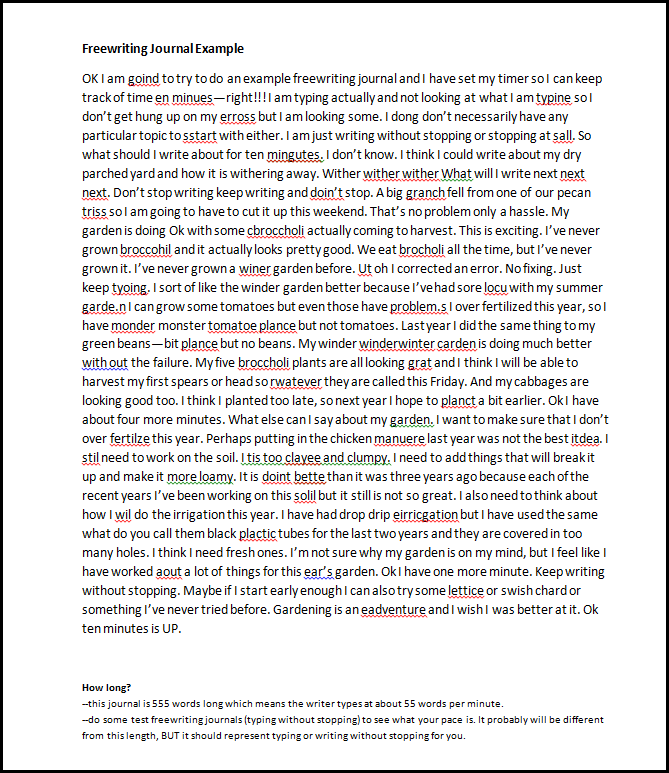

Freewriting Freewriting is a strategy to use either as you are getting started or when you get stuck at any point in the writing process. Freewriting is simple but powerful. When you freewriting, you write without stopping for a set amount of time. As you write, you put your thinking down on the page in its rawest and most chaotic form. Don't worry about any errors or form or "essay requirements." Don't worry if what you write is correct or even makes sense. Keep writing without stopping. Just get your thinking down on the page in a sort of stream of consciousness. The power of freewriting is in its freeness which opens you to discovery and making connections you might not have otherwise. Also, freewriting is like a first rehearsal for re-presenting your thoughts in language, and it will help you feel out your thoughts in language to find the best way of saying something. The scope for your freewriting could be a ten minute getting down of your initial thinking on a topic or it could be a focused freewriting on a problem you are having with part of a draft. You can even do a full freewriting first draft (sometimes called "zero drafts"). When you finish your freewrite, you will want to review it for ideas or phrasings that you may find useful as you move forward with your writing. |

|

|

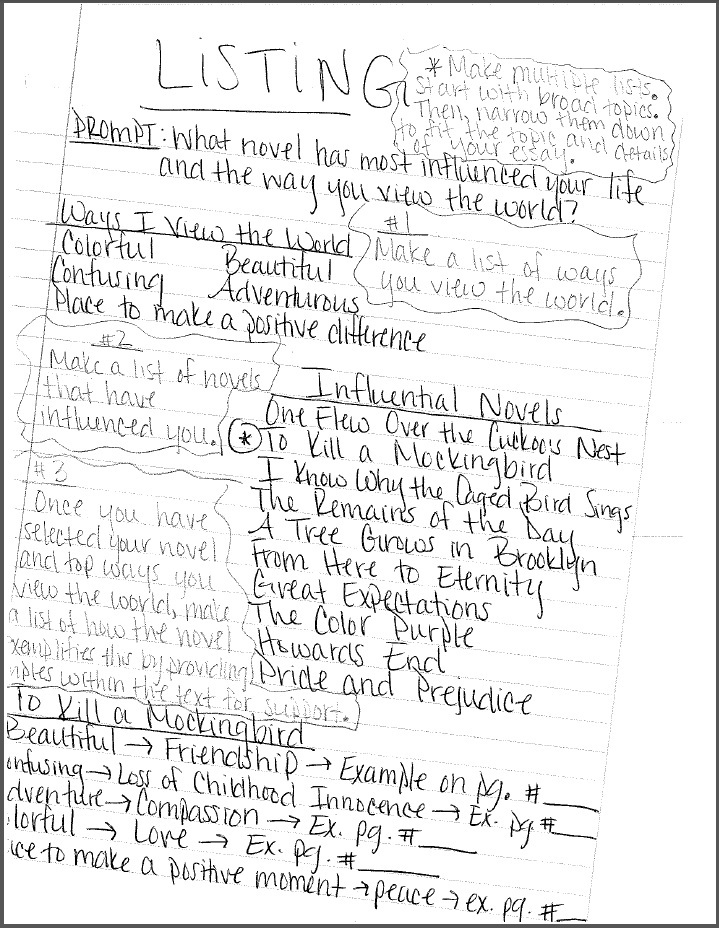

Listing Listing is simple. Just list thoughts, ideas, feelings, observations, details one at a time, line to line, in any order. One analogy to think of when listing is to a jigsaw puzzle. When you list, you try to get as many pieces of the puzzle out on the page as you can like opening the puzzle box and dumping all the pieces on the table. The goal as you list is to get down as many of these pieces as you can. It helps to move quickly and not edit what you put down because some ideas you put down will be great and others not. Don't get hung up on the bad ones. Part of the challenge with listing is to keep going. Inevitably, you will reach a point where your well runs dry. It is at these moments when you should train yourself to push farther. How do you push farther?

Three things you can do after your initial listing:

|

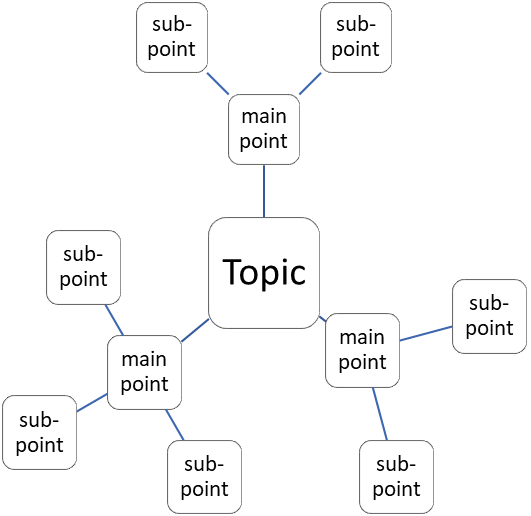

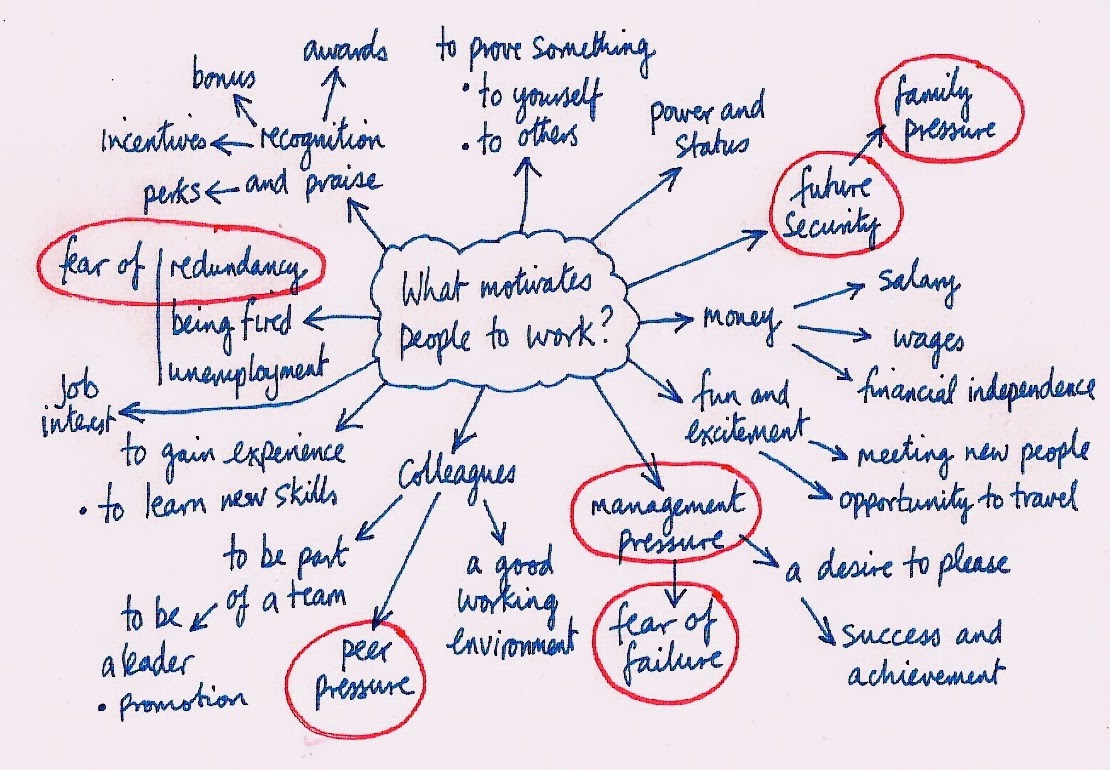

Clustering Clustering is one form of "mind mapping" or concept mapping. Rather than listing, which is vertical and random, clustering is more hierarchical, starting with a central topic or point. As you radiate out, you put down related main points and sub-points. The hierarchical movement is from general to specific, getting more detailed the further you radiate out from the central topic. In outline form, this movement would look like this: I. Topic Clustering, in fact, can be a tool to sketch out your thinking in rough form to find this structure of Main Point (Thesis), Primary Supports, and Secondary Supports which is the common developmental structure of essays (See Development). As you can see from the second example, this initial brainstorming may be all over the place, and you may confuse what is a main point and a sub-point. By clustering your ideas out like this, you can test and discover the possible structure for your eventual paper. In addition to helping make visible the possible structure of your thinking, clustering is a good way to prompt you to seek details because the further out you go from the center topic, the more detailed you get. Since there is not a lot of room in this diagram, you will only be able to write down labels or summaries of these details. For your eventual paper, you may need to create note sheets where you gather and record these details (see Note-taking and Evidence Sheets below).

|

|

|

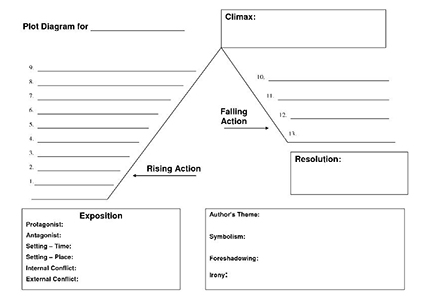

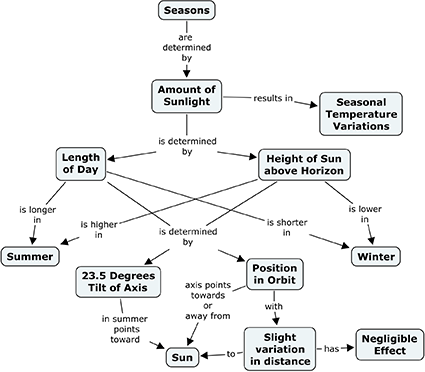

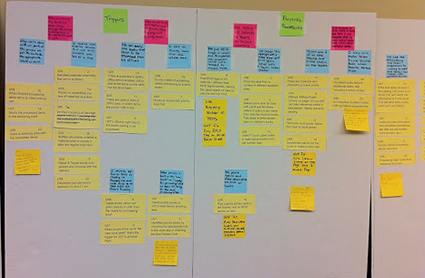

Graphic Organizers and Concept Mapping Whether you use a prefabricated graphic organizer or work more organically, these approaches to brainstorming are about exploring structure and the relationships between ideas. Whereas clustering tends to be hierarchical, these strategies of diagramming ideas help you explore more complex relationships as you analyze a topic. Many of these thinking tools are more about helping your to explore and understand a subject rather than chart our your finished thinking. In other words, these strategies help you find the key insights or main ideas you would then build your eventual paper around. For instance, we wouldn't write a whole paper describing the plot of Hamlet following the Freytab Pyramid's structure. However, by doing this exercise analyzing the plot carefully, we might see something significant we might want to write on--like for instance, the influence of Hamlet's belief and disbelief in the ghost on his actions in the play. Graphic organizers are frequently used with young writers. As this publisher website with 35 free-to-use graphic organizers says, "Use graphic organizers to structure writing projects, to help in problem solving, decision making, studying, planning research and brainstorming." While it may seem elementary to use fill-in-the blank tools like these, they can help all writers to explore the structure of ideas and help prompt you to flesh out these ideas with details. Concept Mapping, or Mind Mapping, is a visual way to represent ideas and the relationship between them. To make a concept map, you write down key words or concepts and enclose them in a circle or square. Then you draw arrows between related ideas along with a quick explanation of why they are related. Many software applications exist to help you do this concept mapping, but a pen and paper work just as well. Another way to concept map is to use Affinity Diagramming. With Affinity Diagramming, you collect notes or ideas and put them down on post-it notes or note cards. Then you begin to physically organize them into groups based upon common characteristics or themes. Because these concepts are on note cards, it is easy to move them around as you rethink groups and what they mean. Then you label these groupings. These labels identify the big picture themes or concepts you could then structure your eventual paper or work around. The notes within each grouping also provide potential details for support you can use. See this article for more on affinity diagramming. Although a strategy often used with groups, affinity diagramming can also be used on your own to make sense of notes and impressions as well.

|

Questioning/Heuristics

|

Asking questions and them seeking to answer them as best you can will lead you places you would not get to unless you asked the question. Questions start with what you don't know. Like many of our other invention strategies, asking questions helps you explore and understand a topic better so that you can develop your thinking. While it can be fruitful to write down any question you have about a topic and then freewrite or list your answers, many sets of questions have been developed that have proven over time to be especially fruitful for understanding the landscape of a subject. Below are a few of the most commonly used sets of invention questions: 5Ws: Analyze the Writing Situation:

Burke's Pentad (exploring motives): Stasis Theory is a four question strategy used in classical rhetoric to analyze an issue being investigated. These key questions help you understand an issue more deeply:

Topics or Topoi

|

|

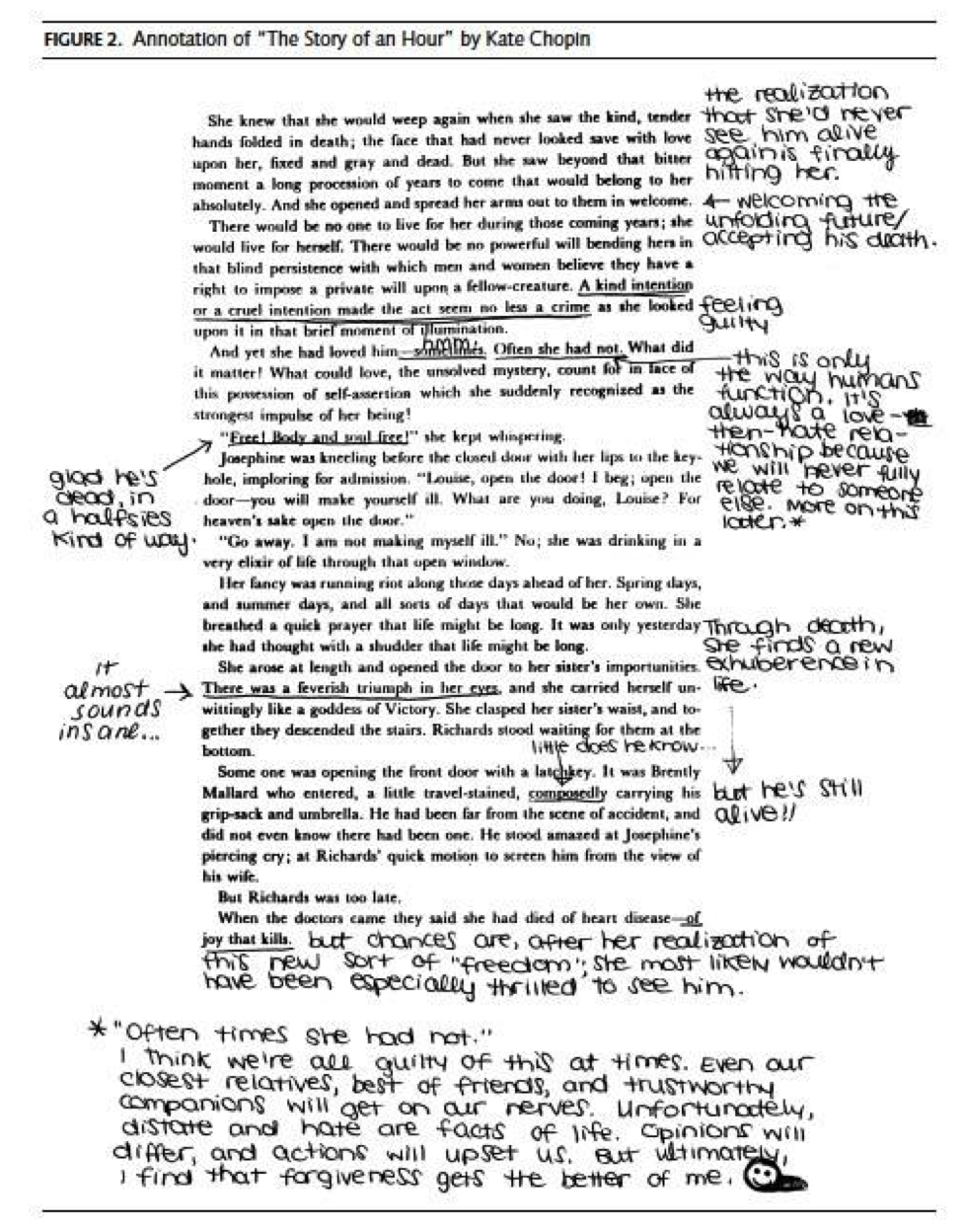

Annotating Most of your learning and writing in college will be based upon your reading. Thus, not just how you read, but how well you read makes a significant difference for your learning and writing. As the Guide for Interactive, Close, Critical Reading states, you must read in college for knowledge, recall, and reuse. That means you invariably are reading for a purpose related to your learning and the tasks of your class. Just as writing is a process, so too is reading a process in which your understanding of a text grows as you work with the text more and more. A key part of this reading process is annotating the text. When you annotate, you not only help to make visible the thinking in the text, but you also record your thoughts and impressions of the text. I know in high school you may have been taught not to mark in your text, but in college, you can write in your text (and even sell the text back). As the Guide to Annotation illustrates, you DO the following things as you annotate and read actively and interactively:

You might underline text you think is important; key signals for the structure of the text; or important people, places, or dates. In the margins, you might record questions you have, make connections, express your reactions to the text, or note similarities and differences. This marginal commentary is like your conversation with the text. These annotations, then, become the basis for you to return to the text to see what is important, perhaps pulling ideas and quotes you will record into notes of the text to use as possible evidence in your writing. See the Guide on Crossing the Bridge from Reading to Writing.

|

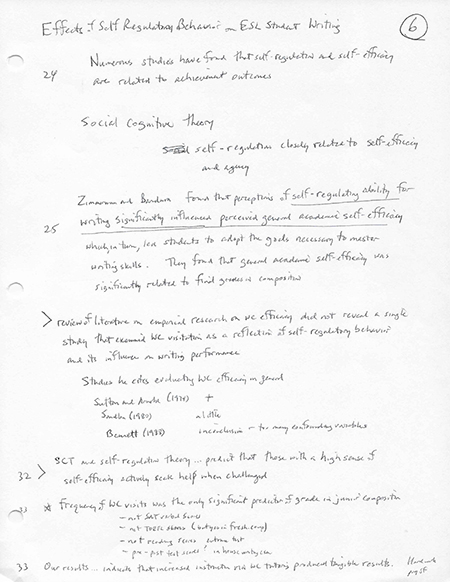

Note-taking Note-taking is an act of collecting. Since, as Donald Murry states, writing is built from an abundance of information, gathering notes is about collecting this information. It is a form of listing what you "note" is important. Thus, by definition, these notes are selections from a lecture or reading of things that are important. Cornell Notes is the most used and popular method for note taking from lectures. Typically used to record important points and details from lectures, Cornell Notes can also be used as a double-entry notebook to take notes from readings. The image on the right is an example of notes taken from a reading. These kinds of notes come from a second reading after close annotation of the text, and consist of selected quotes and ideas from items underlined in the text. Since these quotes may be used later in your text, be sure to record what page number these quotes and ideas come from. The benefits of notes are both in the selection of key ideas and the way they remain visible (and thus memorable) for you to come back to. The notes, then, are a winnowing down of what is important. They become the pieces you can further select, and sort, and order to build your writing piece.

|

|

|

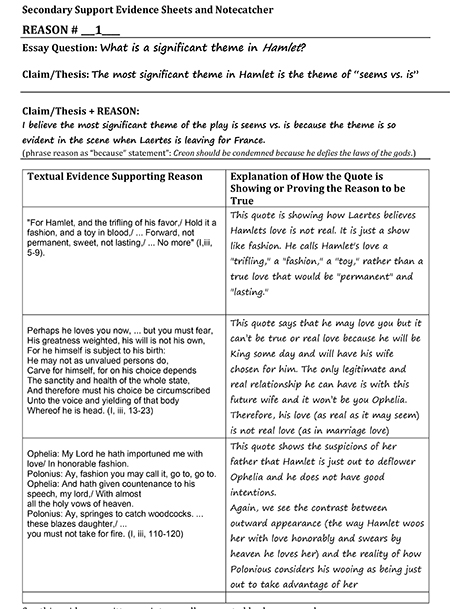

Evidence Sheets/Notecatcher While taking notes might be a first level of collecting important information from sources, evidence sheets or notecatchers are a second level selection of important facts or quotes you plan to use in a paper. You might also collect evidence from your annotations directly into a note-sheet like this. In either case, evidence is collected to support a primary support for your thesis. The primary characteristic of this type of invention strategy is to collect support for a focused point or assertion. Two aspects of this strategy make is both generative and useful. First, you should seek to collect as much evidence for your point as you can. For instance, in the example to the left, the writer seeks to collect as many quotes as she can to show the theme of "seems vs is" in a scene from Hamlet. Although three are listed here, the writer could have found at least five. This copia or overabundance of supporting evidence gives you options as a writer. If your evidence sheet has more textual evidence than you need, you can review the list of quotes and select the best ones and easily see the best order to present them in your paper. The second generative part of evidence sheets is the right column where for each quote you brainstorm ways in which this bit of textual evidence is working to show or prove your point. Often this connection of evidence to the claim is what is missing in essays, so focusing here in an informal setting "off the page" on what this connection is can be extremely helpful. Many students struggle with not just understanding what the quote means but why it matters. Notecatchers or evidence sheets like this prompt you to think through the connections before you begin to formally draft your paper. Then, when you do begin to draft, you can use each Evidence Sheet as a cheat sheet of sorts to write from. You have done much of the difficult collecting and thinking ahead of time in gathering the best evidence and exploring that evidence's meaning in terms of supporting your point. It can make your drafting flow much more smoothly. It also enables you to integrate your quotes much more easily. Along with annotating and taking notes, creating evidence sheets are together powerful strategies for crossing the bridge from reading to writing. Evidence Sheet/Notecatcher --Example

|

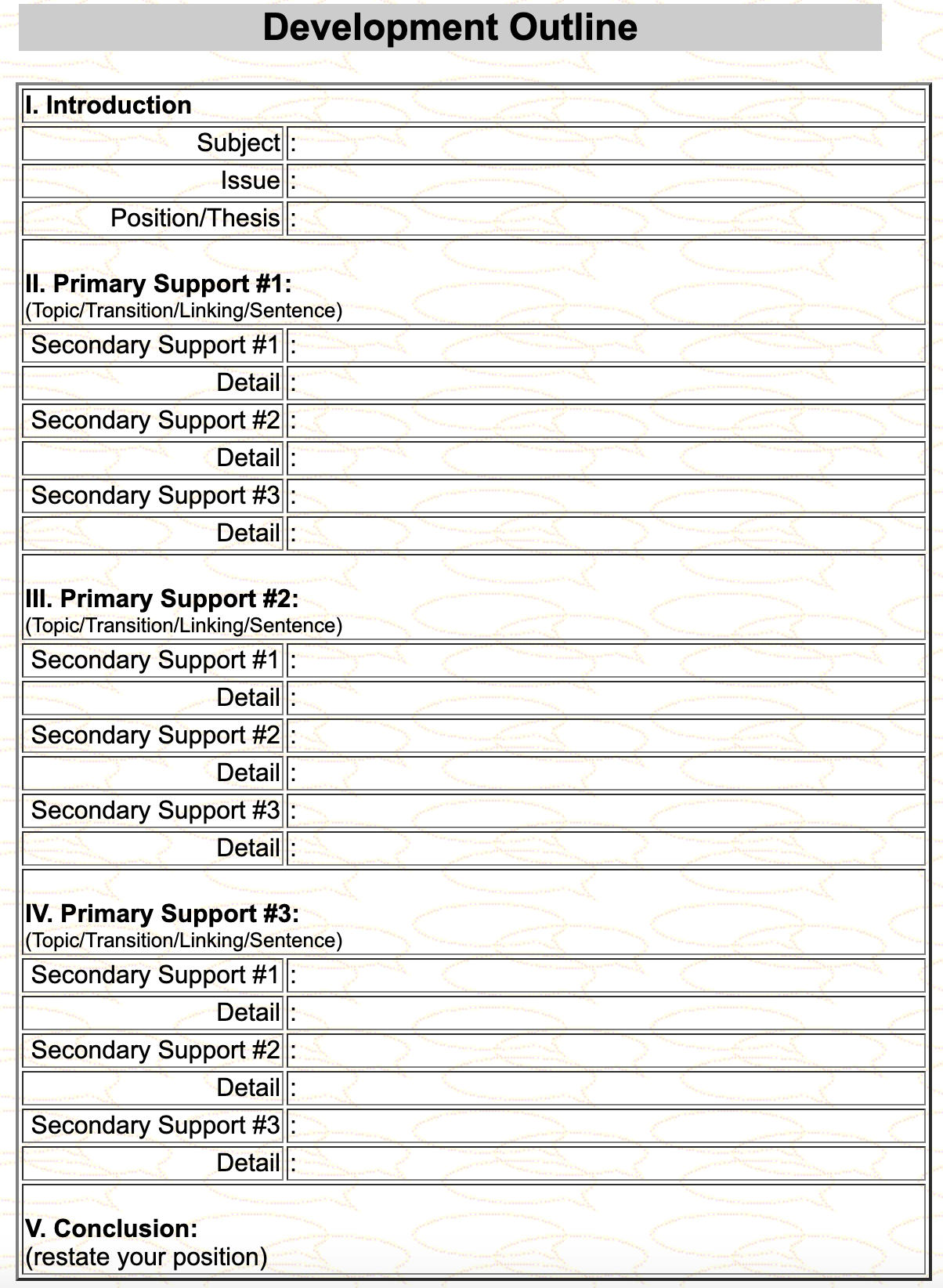

Outlining Outlines help you structure your thinking and provide a guide from which you can write, but few writers can simply whip out a complete and perfect outline. I don't recommend that you start with an outline. Order comes from chaos, so you need to spend time doing more loose brainstorming strategies like freewriting, listing, clustering, annotating, or note-taking before you put together this well-organized and developed structure of your paper. An outline, then, becomes the place where you review the copia or abundance of ideas and evidence around your topic you have collected and generated in order to make choices about the formal structure of supports and evidence you will use in your paper. Because generating an outline takes being at a more finished place in our thinking, many writers don't write an outline before they start drafting. Sometimes writers benefit from starting an initial draft with a mini-outline that only has a sketch of the first level of Primary Supports for the thesis defined. Writing the draft becomes a way of exploring the topic. Then, writers review this draft to gauge if this structure works and the kinds of supports needed. Another approach to outlining is to do a backward outline.To do a backward outline you review a completed draft and outline what you have. This becomes a way of helping you to see the structure of your thinking and support in a draft to help revise it. Development Outline

|

|

Works Cited

Elbow, Peter. Writing without Teachers. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Flower, Linda. Making Thinking Visible: Writing, Collaborative Planning, and Classroom Inquiry. National Council of Teachers of English, 1994.

Lauer, Janice M. Invention in Rhetoric and Composition. Parlor Press, 2004.

Murray, Donald M. A Writer Teaches Writing. 2nd ed., Thomson/Heinle, 2004.

Ritchhart, Ron, et al. Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners. Jossey-Bass, 2011.

Free Web Counter

(Since 1/12/16)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License | Contact Lirvin | Lirvin Home Page | Write Place Home